This brisk and bouncy novel begins with the birth of its titular hero in a forest somewhere deep in Brazil. Right from the get-go he is a trickster, known for “playing” with women’s “charms”. Even when he is little he takes his brother’s girlfriend into the forest to a magical patch of plants that transform him immediately into a prince. And so it goes on, following Macunaíma and his long-suffering brothers Maanape and Jiguê.

Macunaíma is somewhat undone, or as undone as someone with his attention span can be, by his affair with Ci, mother of the forest, who climbs into the sky to become a star leaving him bereft except for the talisman that she gives him. When he loses this and it ends up in possession of a Peruvian giant named Venceslau Pietro Pietra, he embarks for Sao Paulo to retrieve it. He travels the length and breadth of Brazil, and beyond, creating by incident core parts of Brazilian existence, such as the rude gesture he invents when he first encounters the city’s women.

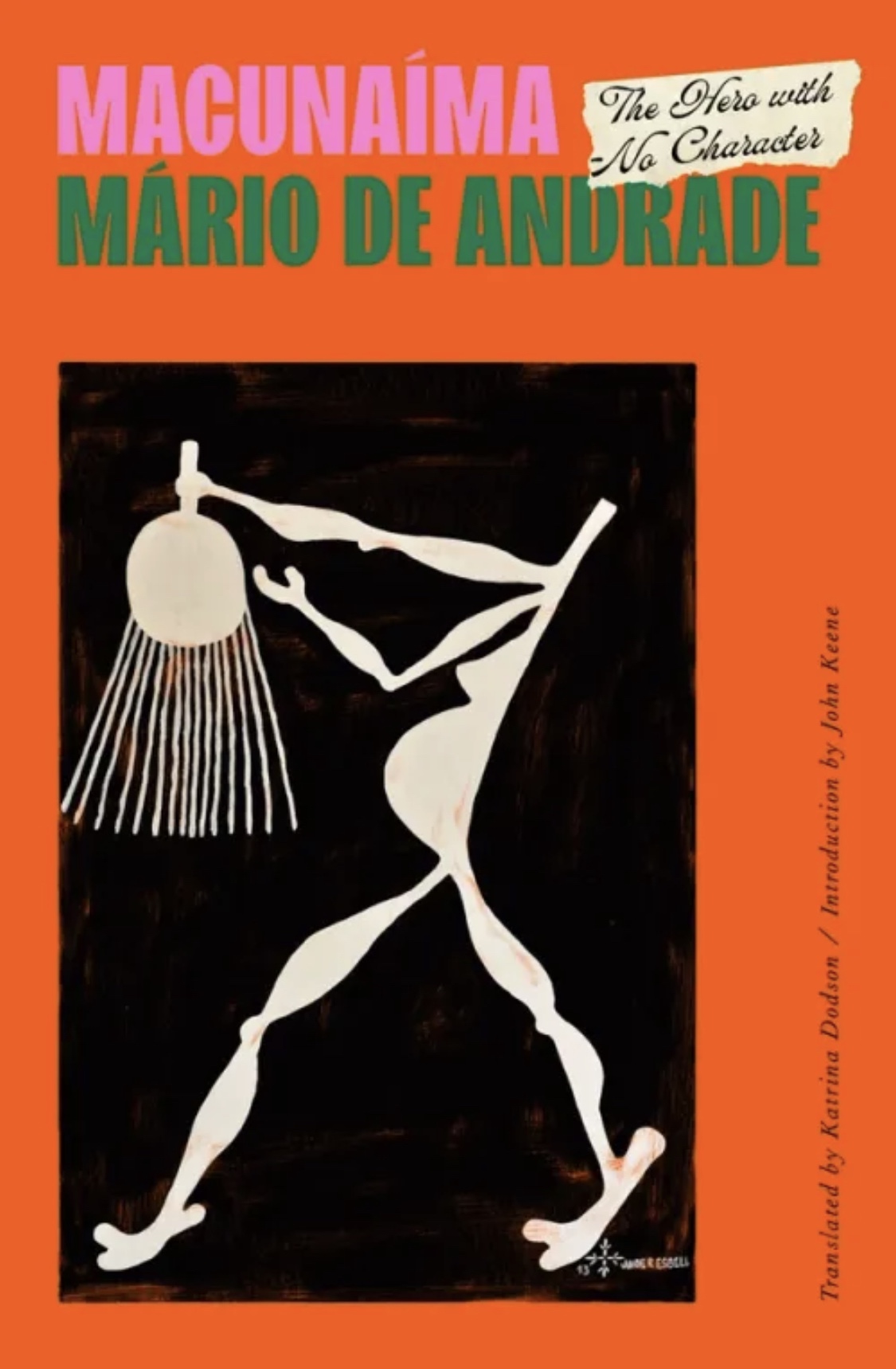

Subtitled “The Hero With No Character”, Macunaíma actually seems full of it. (In unpublished prefaces included with this translation, De Andrade explains that he meant this literally; he wrote the novel in a fit of cultural cringe that his country had no national character). He is a shape-shifter and a fool, known above all for his catchphrase, “Ah! just so lazy!…” which he uses whenever he doesn’t feel like doing something, including, at one point, sex. He doesn’t however change very much: he lives his life of adventures, and by the novel’s end it’s not very clear what exactly has changed.

Perhaps it has something to do with the novel’s ironic stance. Nothing is sacred in Macunaíma; everything is ripe for sending up. Macunaíma isn’t a noble savage but a savage, lazy, idiotic noble. When he sees a larger cowbird exploiting a sparrow, “the hero grabbed a club and killed the little sparrow”, bluntly embracing the exploitative logic of the state. Later he praises the city’s solution to crowding:

The aforementioned thoroughfares are thickly layered … principally with an ultrafine dust that dances about, and daily disseminates a thousand and one specimens of voracious macrobes, which decimate the population. In this manner hence, they have resolved, our elders, the issue of traffic regulation; since these insects devour the meagre lives of the rifraff and impede the accumulation of industrial labourers and the unemployed.

Macunaíma is a riot — a puerile, perverse, absurd and scatalogical just-so story — and a total hoot. De Andrade’s prose, rendered into cinematically vernacular English by Katrina Dodson (“rondayvoo”), is so playful and plenitudinous that it feels like the verdure of the jungle:

Macunaíma plunked down on a riverbank and kicked his feet in the water shooing away the mosquitoes. And it was lotsa mosquitoes black flies no-see-ums gallnippers katynippers sandflies skeeters mitsies maringouins midges gadflies, that whole mess of bloodsuckers.

Notably the only time we get to hear from Macunaíma directly is his letter back to his people, rendered in ridiculously over-the-top courtly prose, the prose of anthropology which would have objectified and exoticised Macunaíma and his people (De Andrade drew deeply on anthropology to create Macunaíma). This shape-shifting, time- and space-bending novel feels like a country wrestling with its identity.

Gay rating: not gay.

1 Comment