Grandmother Eddie Blanket is walking along the riverside path in Brisbane when she trips and falls, knocking herself out and ending up in hospital. She’s cared for by young Dr Johnny, bothered by the journalist Dartmouth Rice who pries her life story from her, and kept on her toes by grandaughter Winona, later described by a smitten Johnny as “entitlement on steroids … or a real live revolutionary”. It’s 2024, with the colonial bicentenary of the city looming, and as Johnny and Winona navigate what it means to be Black in 21st Century Australia, Eddie becomes entangled in the politics of the anniversary.

In the second timeline, beginning in 1840, we meet a Kurilpa family on the banks of the Warrar, the Brisbane River, Yerrin and Dawalbin and their son Murree. They receive news of the white settlers withdrawing: “The Countries are returning to us … the end of the Catastrophe was in sight”. But of course that turns out to be wishful thinking. Fourteen years later, the young Yugambeh man Mulanyin leaves his Country on what is now the Gold Coast and goes to live with the Kurilpa in Magandjin (Brisbane). There he is initiated and works with Murree for the Petrie family, where he meets and falls in love with Nita, their adopted maid. Mulanyin dreams of earning enough to buy a whale boat and return to his saltwater Country with Nita. But the Catastrophe has intensified: Native Police and death squads of settlers murder his kin; the settlement is ever-expanding onto stolen land; Mulanyin must carefully navigate all the white laws that could see him gaoled and executed like the warrior Dundalli. As Lucashenko writes in the afterword, most of the people, places and events are real or based on reality.

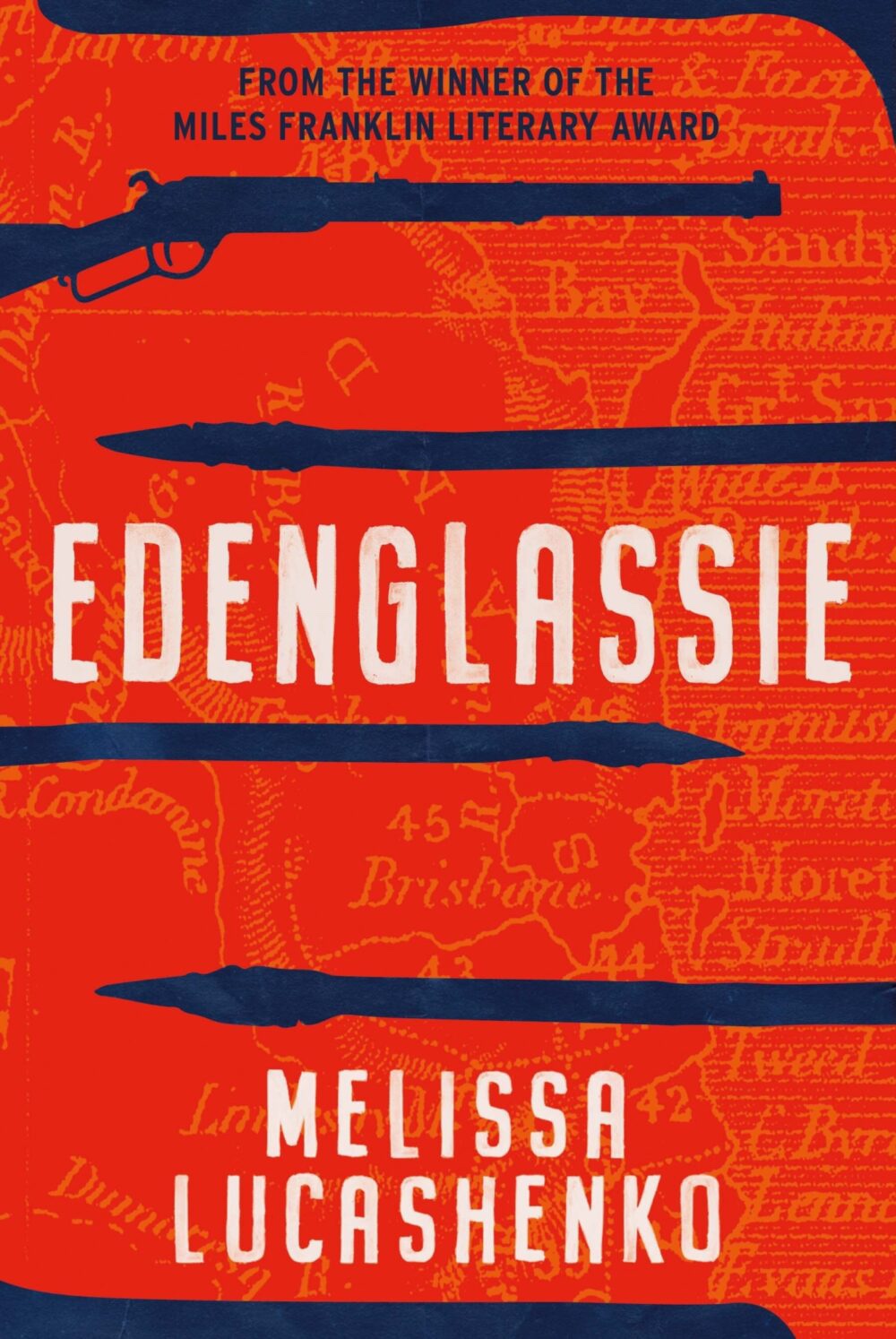

Edenglassie (an early name for one of Brisbane’s suburbs) documents a clash of civilisations, although as it shows it’s rather hard to describe the British governors as civilised. Mulanyin is horrified to discover that the British have no Dreamings that keep them to their own lands. “England was pure savagery!” he decides:

The dagai had bought work with them from their own unfortunate starving Countries, and that was where it belonged, along with other odd ideas like Fences, Debt and Jesus.

In the 21st Century, Winona has a million revolutionary ideas to fix climate change (“ya keep burning the cunt down down till the dumb fucks inside start listening to the science”) and colonisation:

She imagined endless offices filled with endless Blak bodies, mob all around typing emails and having meetings and doing whatever the fuck else office workers did, (not much in her experience), until each Blak body in turn closed their laptop, stood up and walked out the door never to return. Because the whole mob of em had bought back the farm, over and over and over, in their tens of thousands, till they once more owned the continent they had never agreed was lost.

Although more elegiac than Lucashenko’s previous novel, Too Much Lip, Edenglassie is still a riot, its sorrow enlivened by rage and humour, its ideas and plots threatening to blow its confinement to pieces. Her bedbound grandmother reminded me of Geetanjali Shree’s Tomb Of Sand, another tale of taking what is assumed set in stone (age, borders, gender, sexuality) and turning it upside down and inside out. There’s something of Shree’s wordplay, too. “She fell at the maritime museums they said earlier,” Lucashenko writes, “May as well say Murri time museum”, transforming through words alone a colonial and military institution into deep time. Later Mulanyin hears in the word Yahweh the Yugambeh word yoway, yes, and ponders whether he has said ‘yes’ too often. Edenglassie’s two timelines demonstrate that always and forever there were/are other possibilities, roads not taken. That is a liberating idea, but one that needs come with greater scrutiny, ownership and responsibility.

Gay rating: 2/5 for brief nods to non-straight characters and relationships.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.