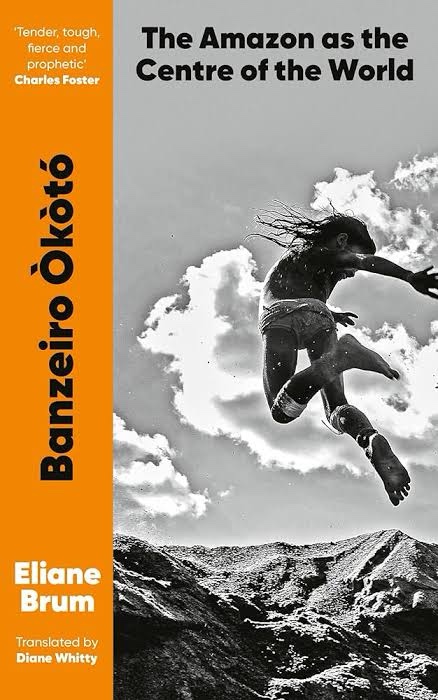

Banzeiro, Brazilian journalist Eliane Brum explains at the beginning of this rich book, is a word from the Xingu region of the Amazon that means “where the river goes savage”. But it is less translatable than that, and nor is it necessarily correct to call this the beginning. The chapter is numbered 11, the following 31, then 2, and so on. “The first sign given by peoples of the forest that their worlds don’t conform to linearity” is their answer to the question of their age, Brum writes, which might be 65 one year and 23 the next. Forest peoples, or forestpeoples as Brum comes to write, encompass not just Indigenous people but beiradeiros, more recent settlers in the forest, and quilombolas, descendants of enslaved folk. These are people who regained or never lost a two-way, reciprocal relationship with nature. They are people who “aren’t in the forest, they are the forest”.

The rest of us — the loggers, miners, cattle barons, land thieves, the extractivists, the capitalists, overwhelmingly white — are deforested, and the future of the Amazon, indeed the future of the world, hinges on our ability and willingness to reforest, to “Amazonise”. Here Brum is talking not just literally about the Amazon and the immediate perpetrators of Amazon deforestation but the whole world, all of us. This is a book that lives between two ways of being and is a manifesto for addressing the ecological catastrophe that we are in the midst of. For Brum the Amazon is not just a suitable metaphor for this epic battle, it is the world and the world is the Amazon. It is a study of what the Amazon does and can mean, and what deforestation in its broadest sense does to people, animals, the forest. It is a provocation, a challenge, an inversion of thinking. Let it swallow you up like the whirlpool of the banzeiro and you might begin to sense its possibilities.

After first visiting the Amazon in the 1990s on reporting trips, Brum moved to Altamira in 2017, its most violent city. It was here in the 2010s that the Brazilian government embarked on the latest paroxysm of Amazon deforestation with the construction of the Belo Monte Dam on the Xingu River, one of the Amazon’s major tributaries. Forestpeoples were displaced, to be converted into urban poor in cities like Altamira, with subsequent symptoms of social dysfunction like gendered violence and youth suicide. “Altamira is ruins,” Brum writes:

Like Brazil, Altamira is a constant building of ruins atop the most monumental of all ruins: the forest that once was there.

Brum incorporates her reportage to tell some of these stories, such as 60-something Otávio das Chagas, born on an island in the Xingu, and subsequently forced off his land by the dam. “I don’t know if you’ve ever seen a man who’s been wrenched,” Brum writes, “A refugee in his own country … the horror of being reduced to the territory of one’s own body”. Although centred around the Xingu and the Belo Monte Dam, in Banzeiro Òkòtó Brum documents 500 years of environmental conflict, from the first genocides of Indigenous peoples, to the opening of the Amazon with the Trans-Amazonian highway during the business-military dictatorship, to the resurgence of deforestation under recent populist president Jair Bolsonaro, which captured the world’s attention during record-breaking fires in 2019 (records which have since been exceeded, although deforestation has declined).

Brum explores in detail the structures and ideas that enable deforestation (and here she means not just the literal destruction of the forest but the whole thing, the removal and murder of forestpeoples, the poverty to which deforested people are condemned). One of those is the grilagem, the system for land theft variously implicitly and explicitly endorsed by government. Another is the perception of the forest as commodity, or forestpeoples as impoverished under the capitalist definition of material wealth. Simultaneously Brum recounts her personal move, not necessarily to the forest, but to an unsettling in-between place. She documents her involvement in activism including the Amazon Centre of the World movement that she helped found in 2019. She describes the impact of the Amazon on her viscerally. The “city body,” she writes, is “accustomed to pretending it doesn’t exist”. Once in the Amazon, “now all 100 per cent comes on at once … city people get sick on their first forays into the Amazon because they overdose on body”. Later when visiting Antarctica she describes the terrifying awareness of the impact of her presence; “It took my days to be really sure I had the right to set foot”. When she visits Terro do Meio, a conservation area near the Xingu:

It was like reaching the beginning of the world, one day before the forest was hit by the destructive power of whites. And it was like reaching me, and unknown part of me, silenced and shoved to the bottomless bottom.

Brum is clear-sighted about responsibility and accountability for ecological destruction; there’s no “both-sidesing” here, you’re either on the side of forest destruction or part of the resistance (one of the most personally damning sections condemns millennials as “the most consumerist, spoiled generation”, a generation that has “refused to become adults because this would mean accepting limits”). She celebrates the rise of climate youth activists, which she describes as a move towards the forest.

It will take you much longer to learn the meaning of òkòtó, a Yanomami word. As translator Diane Whitty explains, such play with language is a large part of what Brum is doing in this book, an impact that is more stark in its original Portuguese where Brum rejected gendered words. The prose — variously poetic, strident, tangled — is designed to trip you up, to let you sit with it and chew on it for a moment, perhaps forming new associations, just maybe looking at things differently.

Gay rating: 2/5 for some queer characters and themes.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

3 Comments