Early in his memoirs, Jeffrey Smart offers a parable. In primary school he was given responsibility for the pencils in the classroom, but abused his power by stealing them for his own use. When exposed and reprimanded by his teacher, he writes that she had “confused Art with Ethics”. There is a lot of Art in Not Quite Straight, and what art it is, recently celebrated at Australia’s national gallery. But as for Ethics? That’s left to us.

Born in Adelaide in 1921, Smart lived a mostly charmed childhood. Introduced to Europe at an early age, he roamed the streets of the city, drawn to its purposeful design, its seaside and hidden bushland. He was compelled to create, and was pitched into the artist’s eternal economic dilemma: how to make a living while having the time to make art. His career was a highly relatable chain of odd-jobs — teaching, criticism, media — that took up more or less painting time, with more or less agony, while his renown as an artist grew. Not Quite Straight is often an account of the precarity of creation: reliance on the largesse of the wealthy, volatile financial schemes, and the occasional sale of art. He is left skint as often as he falls into riches. “My ambition has always been to have just enough money to be able to be free to paint,” he writes, “to paint full time, and to avoid the anguish of being forced to sell a painting when hard up, even if lucky enough to have a buyer.” Published in 1996, the memoir largely resolves with Smart at last of independent means after he permanently settled in Tuscany in 1974.

It’s also very entertaining, enlivened by incident poignant, ridiculous and occasionally harrowing. From Greece to Italy to Turkey, Smart is an observant and self-aware guide of a time on the cusp of modern mass tourism. Judging by the attention he gives it, one of the most pivotal events in Smart’s life was his 1948 journey to Europe stowed away as a kitchen hand on a refrigerator ship, although the terms of his employment rather resemble imprisonment. “I was learning about what unions fight for,” he writes. At one point the ship has to detour to Antarctic water to keep its refrigerators cool because the ballast it had taken on had warmed up too much in the Australian sun.

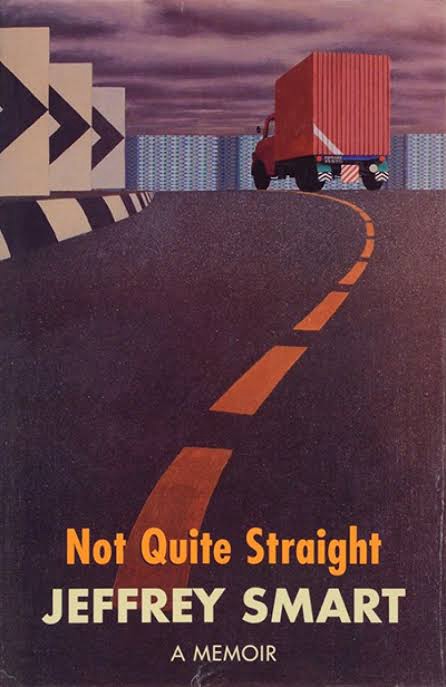

Smart is best known for his surreal landscapes, in which people if they are present are dwarfed by the vastness of the exterior. You can clearly see in them his avowed love of Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca, except he swaps the ruins of the classical and medieval world for the trappings of 20th Century infrastructure — transmission towers, motorways, petrol stations, pipelines, symbols of progress, efficiency, immaculate design. At 23 he travelled to the Flinders Ranges in South Australia paint when he saw “a surreal sight from the bus”:

the single-story hotel and a corrugated iron shed. Of course there was the ruined baroque bank. It was all desert where the wheat had once grown.

Later, in Italy in the 1960s, he is among the first to drive on the new autostrada between Rome and Florence:

Italy was even more scenic from the autostrada — no hoardings were permitted; the only signs were those needed for the traffic and I found them beautiful, they were so well designed.

Ruins have haunted painters since the Renaissance, and Smart, a self-described “frustrated architect” belongs to the same traditions of capriccio and vedute ideate, in which real or fantasy architecture is placed in fictional or exaggerated landscapes. They are nostalgic, mythological, grandiose — a symbol of the might of older civilisations. Often, the buildings are so huge they must have been constructed by giants. But they also contain decay, a warning that all empires crumble.

Twice he receives commissions from resource companies to paint their works, first Rio Tinto in Western Australia’s Pilbara, later BP’s Alaskan oil fields. Whether early forays in green-washing, or simply the whim of the flamboyant directors who were in Smart’s circles, Smart is largely silent on what drew him to these landscapes — he warns that articulating the “enchantment” of inspiration is a writer’s job, not a painter’s. Now they read as prescient; while reveling in the awe of the modern industrial world, he was also documenting the seeds of its destruction.

Smart was always drawn to the mystical and the spiritual. In his youth he was invited to join the local theosophical society; later he visits mediums; experiences revelations in his dreams. He is fascinated by coincidence and cites parapsychology. I think in his paintings you also can see some sort of reverence for a sacred geometry of the world, but its meanings must remain hidden to disbelievers. His politics varied, although he developed at an early age “an unwavering attraction to squalor” and the knowledge that “there was absolutely no justice in the world”. He is deeply moved by witnessing poverty in India, but admits that in his late 20s developed a “social philosophy … a little to the right of Hitler’s Nazism … the theory of eliminating those who could not adapt.” It’s not clear how he overcame such extreme views, only that presumably he did, as his views later in life seem increasingly aligned with the marginalised. He is delightfully willing to settle personal scores, whether through dispatching someone’s character on the page, or, as in the case of the stockbroker who led him to ruin, through art, memorably hiding the words “fuck you” in a mural he was commissioned to paint.

Gay sex was criminalised in Australia for the entirety of the time Smart called the nation home. He discovered his deviance young. The book takes its title from Jeffrey Street near where Smart grew up; like him it was “not quite straight”. In an ecstatic moment of discovering the potency of art and also the male form, he describes encountering a statue of Hercules in one of the city parks. “It was so beautiful, I took of all my clothes, and climbed up and embraced it,” he writes. Later when he shares his first kiss with a man, he was “so emotionally overcome that I embarrassed him”. He seems to always have been drawn to younger men. His first true love was Laurie Mullen whom he met when Laurie is 15; later in life he meets 17-year-old Ian Bent and begins a decade-long passionate, but ultimately ruinous, relationship. While travelling in southern Europe he and his friends pay for sex with young, out-of-work men.

Relationships between older and younger queer men go back to the dawn of time — and are still celebrated if the popularity of Call Me By Your Name is anything to go by. In his circles Smart counted figures like writer Norman Douglas, then 83 with a 14-year-old “boyfriend”, and artist Donald Friend, now recognised as a paedophile who exploited and abused Asian boys. Smart himself seems to feel on shaky ground when it comes to Mullen, who at the time was a particularly vulnerable student under Smart’s care. Although unclear about the precise nature of their relationship until Mullen left school, Smart expresses something like regret, when he admits to engineering a trip away so that they had to share a bed. It “could be construed that I was committing a grave criminal offence,” he writes. Certainly he would have been guilty of gross indecency (which covered any sex between men, a charge abolished in South Australia in 1972), but was he also concerned about his duty of care towards a minor? Grooming was only criminalised in the 21st Century (the law of the time had little to say about sex crimes committed against boys).

Clearly, the law was written and applied asymmetrically, largely concerned with protecting the virtue of girls and women, and oppressing those who deviated from sexual norms. It is all too easy to cast stones from our time when queer men in Australia are mostly equal before the law, and all too hard to imagine the agony of living under such oppression, but neither I think should preclude scrutiny. Smart in his memoirs is avowedly not interested in defending himself, or others, which endears. It’s up to us what we make of his testimony.

Gay rating: 5/5 for queer themes and relationships.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.