“Can people hear me think? Let them,” the narrator of this short-but-potent novel proclaims. She shares her name, Sanya, with her author, a hint of the complex dance of words and meanings that she plumbs.

We are cast adrift at the beginning, entering Sanya’s world as she is entering a psychotic episode. “This sudden fear of brown,” she writes, “I was surrounded by brown things”. First she goes into a community house for care. When she leaves, she goes to the university library to continue her research, a PhD in psychology into language and childhood development, which she paused when she had her first episode of psychosis many years earlier. But apparently she’s not meant to be there, because a security guard calls paramedics and she’s taken to hospital. Later, when she checks herself out, she is returned there under the duress of the cops. The bulk of the story follows Sanya as she navigates this period on a psychiatric ward.

The early sections are disorienting and confusing. Sanya is an entertaining and erudite guide through her psychosis, the coherence of her internal narrative contrasted with the irrationality of the external. It’s where they rub up against each other that things become uncomfortable, as the people around her interact with seeming care and concern and, occasionally, force. Sanya becomes fixated on details: how she seems to notice a particular time, coincidences, is sure that she’s receiving coded messages, if only she could understand what they’re saying. She experiences paranoia, feelings of danger everywhere, a house’s open door a sign that “something’s going on here”. With the muscularity of Rushdi’s writing she compels us to wonder if she is in fact onto something.

When the police come for Sanya, they tell her “we’ll take you nicely, we won’t put handcuffs on you,” but the threat is clear. In hospital she makes known her objection to medication. When she is given an injection, she writes, “I feel I’ve been raped. The needle wasn’t a needle but something else”. More amusing is the doctors’ hysterical prescription of “Lithium! Lithium! Lithium!”, as if addicted to the substance themselves. It is an affecting critique of carceral care. In this theme, and its play with narrative (much of the speech is rendered as script, drawing attention to the performance), it reminded me of Pip Adam’s recent Audition.

Sanya’s research has led her to advocate for a different form of treatment, “proper help, one based on conversation, not medication.” In the healthcare system, she is confronted with “the trap of an imposed language”, one that doesn’t make sense to her. “Those who speak the same language often introduce complexities and nuances into their discussions by virtue of using the same language,” she explains. Treatment based on conversation, she argues, “inspires discussions on subjects with nuance and depth, a path that may look superficially difficult but in fact leads to freedom.”

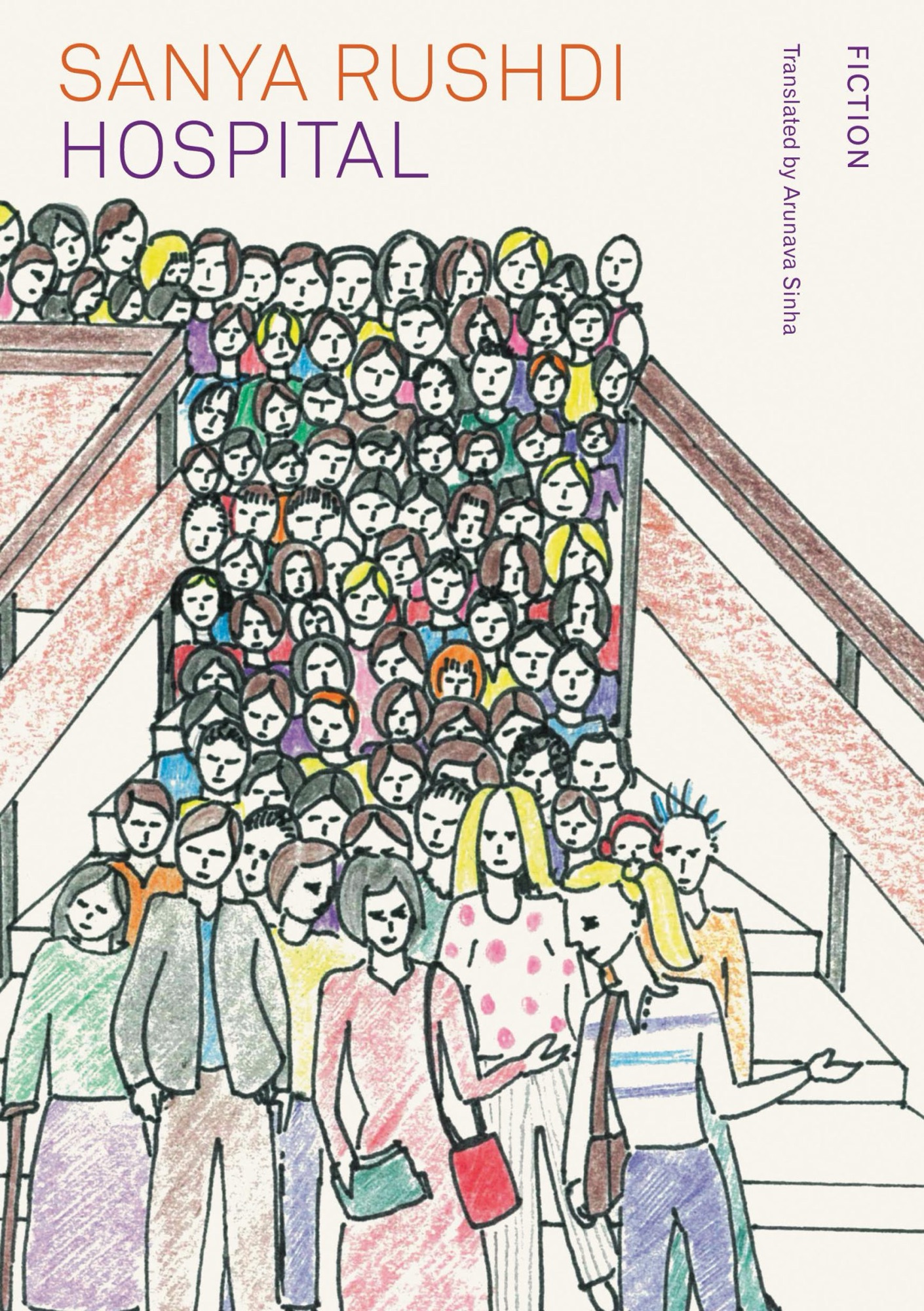

Rushdi fiercely demands we consider the freedoms granted and owed to people with different minds, and how they are taken away by force and by convention. Sanya is fascinated with the behaviour of crowds and flocks, the logic (or otherwise) that drives groups of organisms to move as one. This collectivism she conceives of as an oppressive force:

those who are by nature gentle … are being forced to lose their individuality repeatedly to those who are harsher or have a more developed ‘self’ … love and inability might be considered weakness in such societies.

Hospital is the mind as a meaning-making machine, inherently generative, but not always aligned with the expectations of society at large. Sanya is at her most powerful when she rejects the norms of the sane and wonders how those classed insane offer ideas for reshaping the way we relate to each other. To be lost in one’s thoughts “must be very liberating”, she writes; “Why do I have to explain anything to anyone?”. In hospital she muses:

I think the most unusual people in the city are in this ward. It’s a unique opportunity for me to learn about them — who knows, we might be able to contribute to one another’s work.

In Hospital, Rushdi delineates the forces that marginalise people with different minds, while offering a glimpse of a world with more liberatory kinds of care for those who don’t fit the mould.

Gay rating: not gay.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 Comments