There comes a moment that all of us have to face eventually, that moment when you can no longer avoid facing up to the task at hand, the confrontation with the detritus of living that accumulates in homes, the “stuff”, “clutter”, “rubbish”, “contents”, “remains”, “leavings”, “shit” and “crap” as it is variously titled in this short novel, whether a spring clean or a move or, in this case, preparing a dead parent’s property for sale. So it is for the artist narrator of Wall, who is never named, but we know shares the name of her author because she is accused by her nemesis of making art about anorexia that is “doing nothing but cynically working with what my name suggests”.

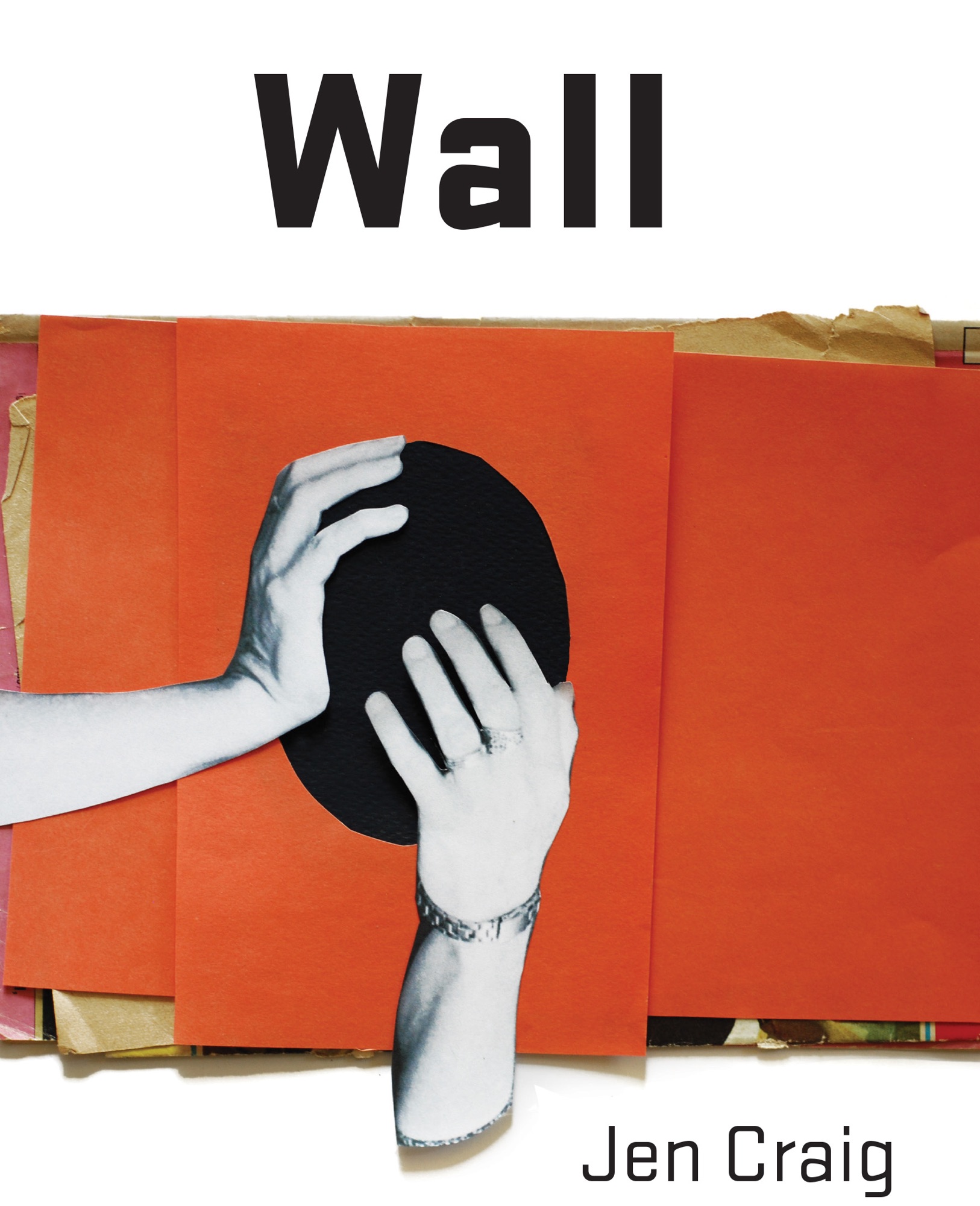

So Jen is in Chatswood, Sydney, facing up to the disorder of her father’s home, standing in the hallway, barely able to answer what she is looking at, let alone what to do with it. Back home in London she had promised her former teacher-turned gallerist Nathaniel Lord that she would construct from her father’s leavings a grand installation in mode of Chinese artist Song Dong, a proposal that is in turn designed to distract Lord from the artwork she is meant to be completing, a series of panels of carefully assembled objects called Still Lives that will ultimately be fitted together to create the Wall. This novel is a book length examination of the dangers of telling people about something you’re working on and of the idea that the best way to avoid completing a project is to start a new one.

In Sydney, Jen is also sucked back in to the drama between her two art school friends and former housemates Sonya and Eileen. Sonya has turned against Jen for some reason; we learn that Eileen has recently fled her home in the Blue Mountains, leaving her husband and daughter behind, and Jen is drawn to assist. The three of them were infamous for an artistic intervention at school about anorexia, which Jen suggests is a response to their feelings of powerlessness in their surroundings. In Jen’s case, this is her father’s hoarding of objects in the house, his own mania for projects and conspiracies which he collects in his mind, and his inability to communicate with people except to speak at them about said projects and conspiracies. It drives her mother to despair. When she has a stroke, Jen observes abjectly, she is found amongst “damp-seeming boxes” and “fungused insoles of numerous shoes … flipping like drying slugs”:

lying as if she’d just been down on her knees looking for something among the “incredible state of the kitchen”, or so a neighbour had told me at the funeral — my mother’s fingers stretching out in the darkness and quivering, he’d said — “still alive” — as if she were trying to grasp, or at least to remember, the thing that continued to elude her (my dad having fetched this neighbour because mum had been “looking a bit strange”, as he apparently said).

It is a deeply painful, grotesque and humane depiction of the tyranny of kinship — and Jen too has her own compulsions and elisions that she alludes to without ever quite coming out and saying directly. Addressed to her partner Theun, Wall is narrated as a confession in sentences and paragraphs that wind on and on, tripping over themselves, interrupting, looping back over past events, but what exactly Jen is confessing you may have to continue pondering after the final page. What is inarguable is the astonishing subjectivity Craig has articulated in prose, a declaration and plea for understanding of selfhood.

She also suggests that on completion of the Wall and the Song Dong project that she will finally be “post-anorexia”. So Wall investigates the impulse to create order from disorder, to apply meaning through arranging, recontextualising, whether objects or relationships or, indeed, narrating it. Craig allows for this pathologising of art, but also the ecstasy of its creation, as when Jen is on a roll, “smaller and smaller the pieces were becoming. Looser and looser. The energy I was discovering in making the work. It was like flying … as if I were just a fat and flightless pigeon that, by accident, had discovered it could fly.”

Gay rating: 1/5 for several fleeting queer characters (I think).

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 Comment