I have fond memories, as a kid, of watching my grandma perform as a part of a women’s variety troupe in the local RSLs and community centres. Although the adult humour must have gone over my head, the outlandish characters and funny songs and dancing reliably had us kids in gales of laughter.

I was thinking about this while reading Sharon Connolly’s history of the entertainers in her family, particularly her great-aunt Gladys and her grandmother Elsie. Both were active in the golden age of vaudeville, the era before radio, film, and TV when variety theatre was the form of popular entertainment.

Connolly’s story starts in 1864 with her great-grandmother Mary Agnes, a music teacher in Sydney who also performed burlesque as Claire Delmar, leaving her first husband for the road. Her second partner — father of Gladys and her brother Keith — was a showman and something of a conman too, using several aliases to give debtors the run around. “These were times,” Connolly writes, “in which women might dare to dream of more public lives.” The theatre offered an opportunity to realise those dreams.

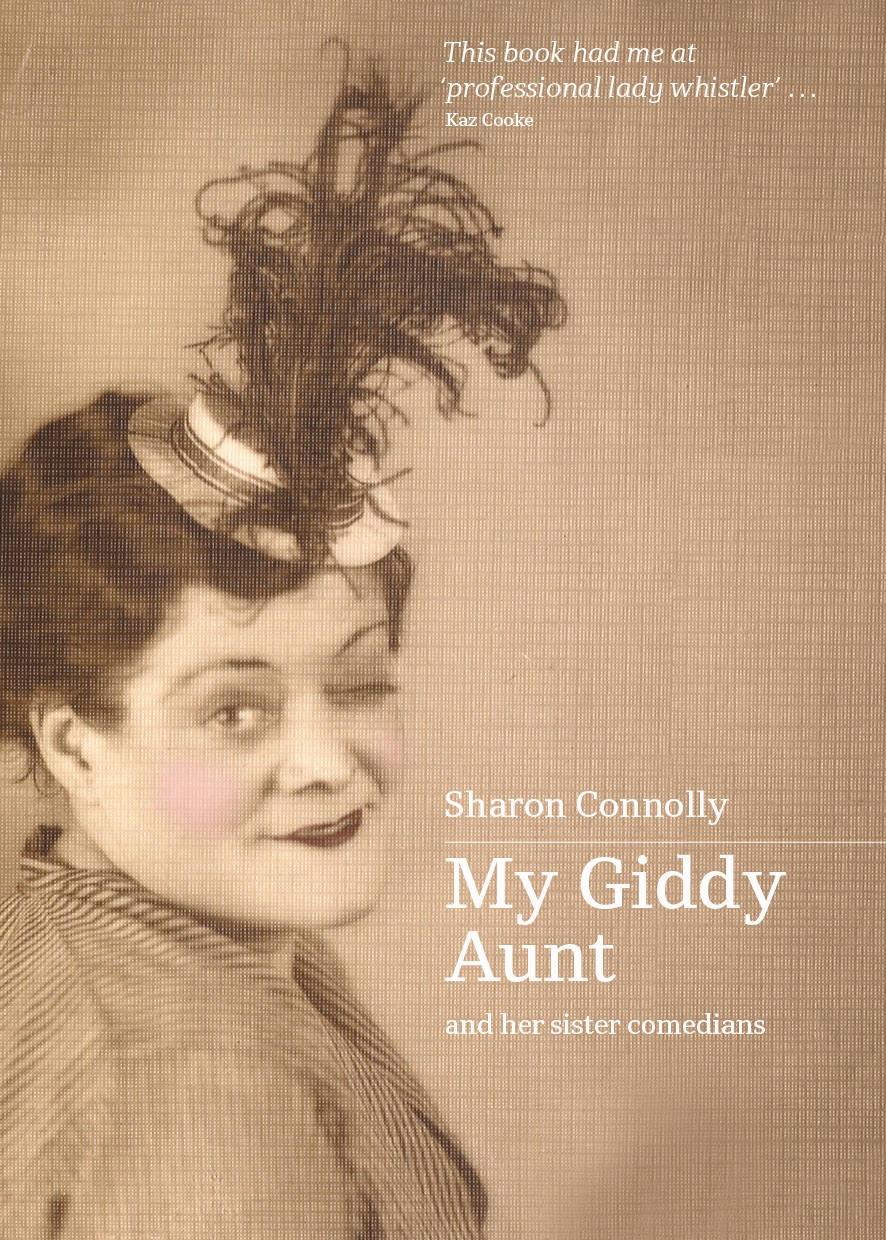

Claire Delmar was the founder of a dynasty of entertainers, “a family tree more like a thicket — of maiden names, married names, false names and stage names”. Gladys took to the stage at age six, at first playing racist caricatures popular at the time. Later, she became a “tango girl”, performed in “revusicals”, did “grotesque dancing”, played the “flapper” in the 1920s, learned the sax, and, most winningly, became a “siffleur”, or professional lady whistler. Such were the variety of acts available to women on the stage. She worked alongside Keith, who longed for “straight” parts (ie, not comedic), and his wife Elsie, Connolly’s grandmother. My Giddy Aunt is a comprehensive document of a forgotten world, drawing on photos Connolly was left in a zither case and access to newspaper articles digitised through Trove.

At a time when women were expected to be housebound, the stage offered certain freedoms. Some women performed as men. One hysterical 1918 article criticising male impersonator Effie Fellows screamed:

The feminine invert goes in for manly games, wears her hair short, and takes to men’s occupations in general. She satisfies her pathological appetite by masturbation which, if occasion offers, is mutual … Women of this kind have been known who held sexual orgies, and induced a whole series of young girls to become their lovers by initiating them into the practice of MUTUAL MASTURBATION.

Which may be the most effective ad for lesbianism ever placed in an Australian newspaper.

Nonetheless, the stage had its limitations. “Girlishness was a vital prerequisite for women hoping to succeed as performers,” Connolly writes. As today, working in the arts was precarious, buffeted by the vicissitudes of war, economic hardship and waves of new technology. Connolly’s female ancestors sadly came to hard ends, each institutionalised for mental illness as their careers came to an end. Elsie received a leucotomy for her “obsessional state”, a surgical procedure that was recommended in part as a way of managing a “psychopathic husband who cannot change and will not accept treatment” (her husband Keith became a rage-fuelled alcoholic). “They could do little to adapt to a culture largely uninterested in mature women,” Connolly writes.

What did happen to vaudeville? Its golden age may be long gone, but it continues to survive, in drag and fringe shows, it’s gone onto the screen in sketch comedy, and it’s still travelling around communities in troupes like my grandmother’s.

Gay rating: 2/5 for some queer themes.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.