War provides cover and opportunity in this meticulous historical novel. At its opening we meet older married antipodean couple Olive and Norm passing through Lincolnshire, “bomber country”. Both served in England during World War II, and find the country “unrecognisable”, they “kept slowing … to cast anxious looks at the horizon”, the transmission towers now “as effective a barrier as barrage balloons”. They stay in the cottage where Olive was once billeted, visit the crumbling aerodrome where Olive served in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, working the radios that guided squadrons of soldiers safely back home after bombing raids in Germany. It was there that Olive witnessed something extraordinary, “the sight of a wide-shouldered, long-legged girl jumping down from the wing of a Hurricane”.

The girl is her childhood best friend Evelyn MacIntyre, a member of the Air Transport Auxiliary, delivering planes between depots. A notorious young woman, Evelyn once stole her brother Duncan’s cricket whites to play with the boys, and has continued in that fashion with gusto. Duncan was later killed when his plane was hit, but not memorialised: “immediate and longstanding circumstance forbade” talking about him. What could he have done to be consigned to disgrace and erased from the Allies’ proud military history? Prompted by the arrival of Duncan’s captain’s diary (“keeping a diary was against King’s Regulations”, Olive notes prophetically), Olive revisits her youth and we learn of the death- and law-defying activities of this group of young women and men.

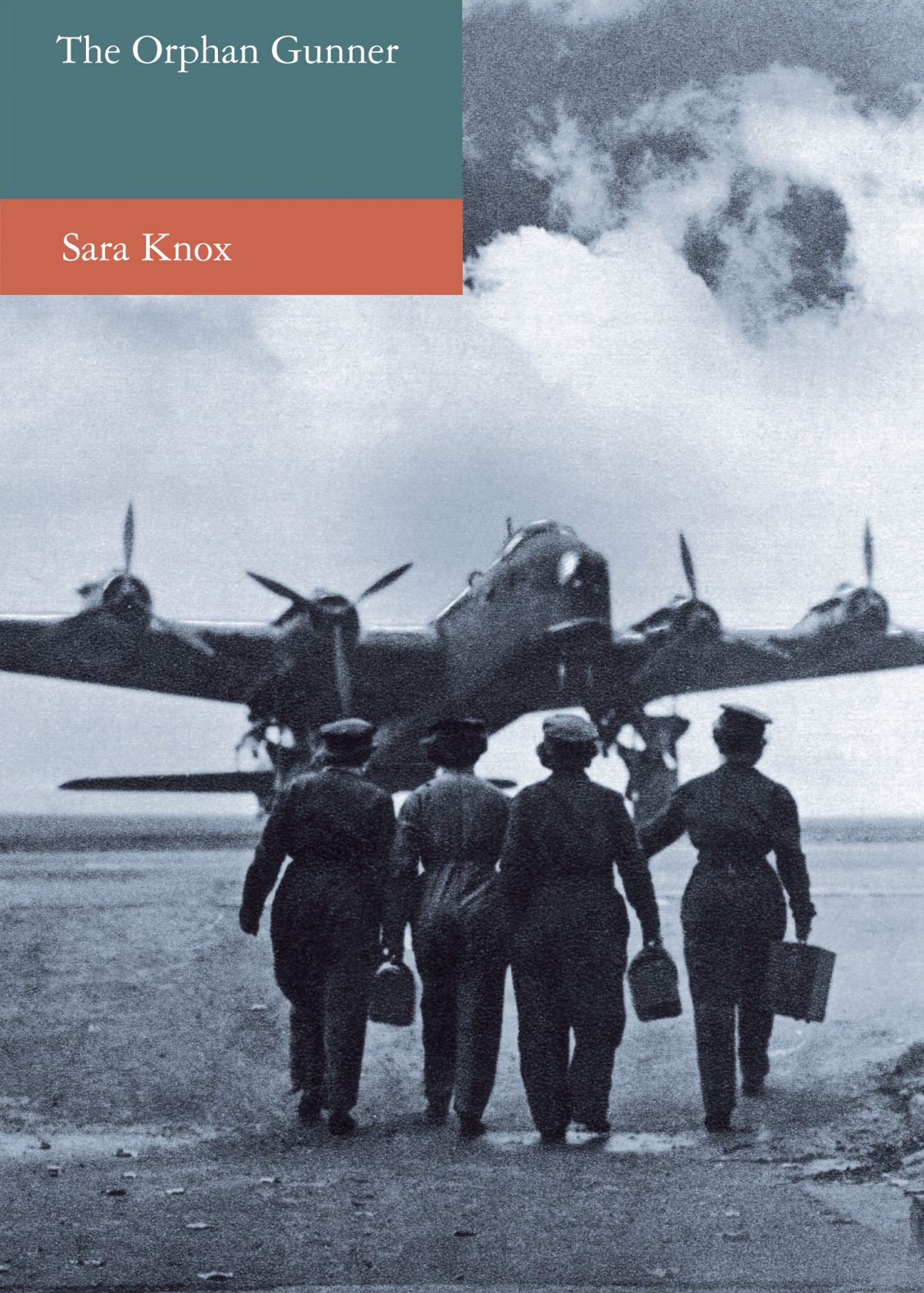

For most of it, The Orphan Gunner soars effortlessly, a breathlessly exciting but understated chronicle of the war machine and the people employed to keep it running smoothly while somehow carving out a little space for their own dreams and desires. Part of the exhilaration is Knox’s delivery of the information required of a war novel: the machinations of various military divisions and the forgotten technologies that are usually reserved for the most avid of aficionados. How it wears such detail so lightly I can’t quite explain. If it wobbles slightly on the landing— a melodramatic climax that stretches belief a little, despite some grounding in actual events elsewhere — it is in service of bringing to life the untold stories of people like Olive, Evelyn, Duncan and the bomber crew LQ-Love.

World War II has been called the “great coming out”. Queer people, freed from the confines of staid peacetime norms and brought together in single-sex communities, found each other and found ways to realise their queerness on a grand new scale. Knox delicately explores these tentative yet impassioned forays in The Orphan Gunner. Evelyn and Olive’s affair is a game of cat and mouse — or perhaps a dog fight — all feints and bluffs, tests of strength and endurance, tentative engagements and evasions. I don’t think a single explicitly queer word is uttered by the characters in the novel (except by the authorities). It is all implied, as hidden in the text as in life. It is all the more passionate for it; a couple of words become ecstatic, a single line in a letter — “a night not spent vying for leg-space” — might ruin you.

For just as war perversely provided a moment of creation for queers, it also contained the potential for destruction. Knox, whose research interests lie in death and violence, brings a laser focus to the mental gymnastics required by those living through horror. The whole thing rests on an ability to avoid acknowledging the reality of what’s going on. It lends the novel an air of lightness and humour evoked by the “NAAFI patter they’d used throughout the war”. Yet sometimes reality becomes unignorable. On meeting a zoo keeper who has been tasked with gassing his charges, Olive finds “she had an urge to find the first open space she could and lie down with her face in the dirt”. Later a rare moment of uncensored feeling makes its way to them through a letter from Duncan. Evelyn responds:

I’d have been happier if Duncan hadn’t committed to writing that he’d seen his friend weep. And I’d have been happier if his friend wasn’t inclined to weeping.

Whether desire or fear or grief, feeling must be pushed down, locked away, maybe one day to be revisited in safer circumstances. With grace, The Orphan Gunner lets a little of it out.

Gay rating: 5/5 for queer characters, relationships and themes.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 Comment