It’s spring 2020 and the city of Melbourne is emerging from its second period of lockdown, 111 days including however many days of Stage 4 restrictions: movement limited to a 5km radius, a curfew between 8pm and 5am. The family at the centre of this austere novel is in stasis. Not just because of the pandemic restrictions, but because of grief; their six-month-old baby Ruby died four years ago in a tragic accident at home. Mother Amy is in serious second-book doldrums, her husband Jin has lost all connection to his work as an emergency physician and is paralysed with indecision about home renovations, and 10-year-old daughter Lucie is having intrusive thoughts about all the ways the people she loves can die. Even if some of the characters find reflection in the quiet, it’s clear that this stasis is a kind of purgatory.

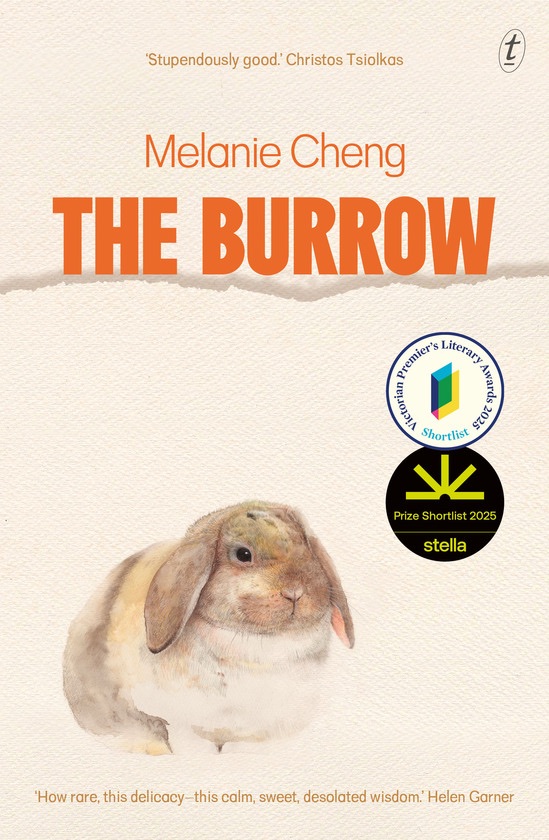

But perhaps spring offers a thaw. The lessening restrictions coincide with the arrival of Pauline, Amy’s mother, and a baby bunny purchased by Jin and christened Fiver after the character in Watership Down. “Perhaps this was the purpose of pets,” Pauline wonders, “To provide a buffer between humans who had forgotten how to talk to one another.” A rabbit’s usual home, Lucie reminds us, not a hutch but a burrow, and Melanie Cheng uses her well-chosen setting to explore her characters’ needs for shelter and care.

Cheng lets the obvious metaphorical possibilities of the baby rabbit seep through The Burrow — its pathetic fragility, how it is unvaccinated against calicivirus, how the slightest stress could kill it with a heart attack — although she warns that “a pet was not a child” because “people replaced pets”. With clinical observation, she examines grief in the bodies of her characters. “Sentimentality” declares Amy, “is death itself”. The Burrow doesn’t exactly swerve emotional paroxysms, and it certainly doesn’t need to emphasise the horror of what has happened to the family, but there’s a curious lack of mystery here. Characters know themselves as they know the world, with a detached gaze. If there is complexity it is reducible. But perhaps that too is the work of all-consuming grief. At its best The Burrow offers a small glimpse of the wildness that lies beyond.

Gay rating: not gay.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.