“This story is addressed to inverts”, the narrator(s) of this gleefully perverse novel interrupt near its opening (who are they? Sailors, lovers? They often seem to be a rather horny Greek chorus). Inversion was the somewhat-sadly-discarded theory that explained homosexuality as queer men taking on the psychology of a woman, and vice versa. It’s just one of the terms thrown around to describe this cast of queers: “nance”, “quean”, “brown-hatter” (use your imagination) and even “homosexual” itself. But whether any of them would subscribe to our contemporary identities of gay or straight is part of the joy: Genet evokes a whole mysterious and now inaccessible queer past. What wonders or horrors might emerge from the fog?

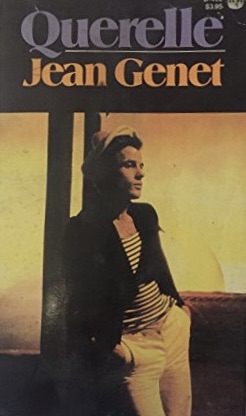

Querelle begins with an ode to murder, to the sea, and its seafarers (and particularly their uniform, “the tight-fitting folds of his jumper and the more ample folds of his trousers”; the film adaptation is the inspiration for Gaultier’s sailors). So we are introduced to the eponymous sailor Querelle, Georges “Jo”, recently ported in the perpetually foggy French seaside town of Brest. Querelle, 25 years old, plies his trade smuggling opium between the ships and the local brothel, La Féria, run by Nono and his wife Madame Lysiane, with whom Querelle’s brother Robert is having an affair. Nono is in cahoots with police officer Mario, who is informed and loved by the teenage urchin Dédé. Meanwhile Querelle’s lieutenant Seblon (the only “real” homosexual in the book, according to the narrators) writes lustfully in his logbook, and 18-year-old mason Gil commits an act of violence in defence of his reputation.

So much for the plot of Querelle, which unfolds not necessarily as a whodunnit, but who’s going to get put away for it. Most of Genet’s words are taken up in gesture, feeling, the way two people’s bodies behave in space towards one another. There is a lot of fighting between men in Querelle, which often seems to be sex, such as when Mario pulls a knife on Querelle and “the blade was white, milky, and almost a fluid substance” (Querelle takes our calls to “fuck the police” and “be gay, do crime” to their literal conclusion). The book’s most lovingly observed fight is between the two brothers — and it’s not just Madame Lysiane who sniffs something fruity. The murders themselves sometimes seem to be allegorical, an ecstatic expression of power and desire, except when they are just murders. I’m reminded of Brando in Hurricane Season, whose desire for his friend Luismi is one of “fucking and killing each other, maybe the two things at once” (and Melchor’s character’s are great examples of contemporary Querellians).

Murder; gay sex: Genet gives both the same languorous and brutal treatment. There is much musing on whether a real man can take it up the arse, or is made a woman by the act, especially should he enjoy it. Sex is domination; in the hierarchy of patriarchy, it seems that the most alpha thing a man can do is to fuck another man. Sodomy may have been decriminalised in France in 1791, but sex between men could still land a person in gaol until 1982. “The reader may regard [this book] as a series of adventures unfolding in the deepest, most asocial recesses of his soul,” write the narrators, daring you to enjoy its perversity, “Whether or not the reader is to escape sin will depend upon how he reacts to the words by of the text”.

Genet steeps his characters in a dense fog of meaning, but despite the dank and misty setting, the writing is fervid and combustible. Amid the esoteric epistemological posturing, the dialogue is joyfully earthy, rendered in all its glorious vernacular by Gregory Steatham. Whether insults —”I’ll piss up your arse and wash your brains out”; “fuck my parents, they’re shit-bags” — or come ons — “if it’s really so good, give us a wrinkle” — I will immediately be incorporating them into daily use. Like the straight men dimly cognisant of “the existence of a world at once abominable and miraculous, the brink of which any of them might be hovering,” Genet throws us into the sea. Maybe we’ll emerge transformed.

Gay rating: 5/5 for queer characters, themes and explicit sex.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

2 Comments