This collection of poetry, collage and photography is arranged as eight sequences. These are indexed by the colours of the rainbow, as if spectra of light separated by the facets of a crystal, and like such spectra, they suggest a whole that cannot be seen directly. In their attention to shape and geometry, these sequences are rather crystalline. Crystals are things of great beauty, but with their hard, refractive surfaces the meanings they can hold — which always seem to be elemental and indelible — are elusive and tricky. So it is with Li’s poems and images.

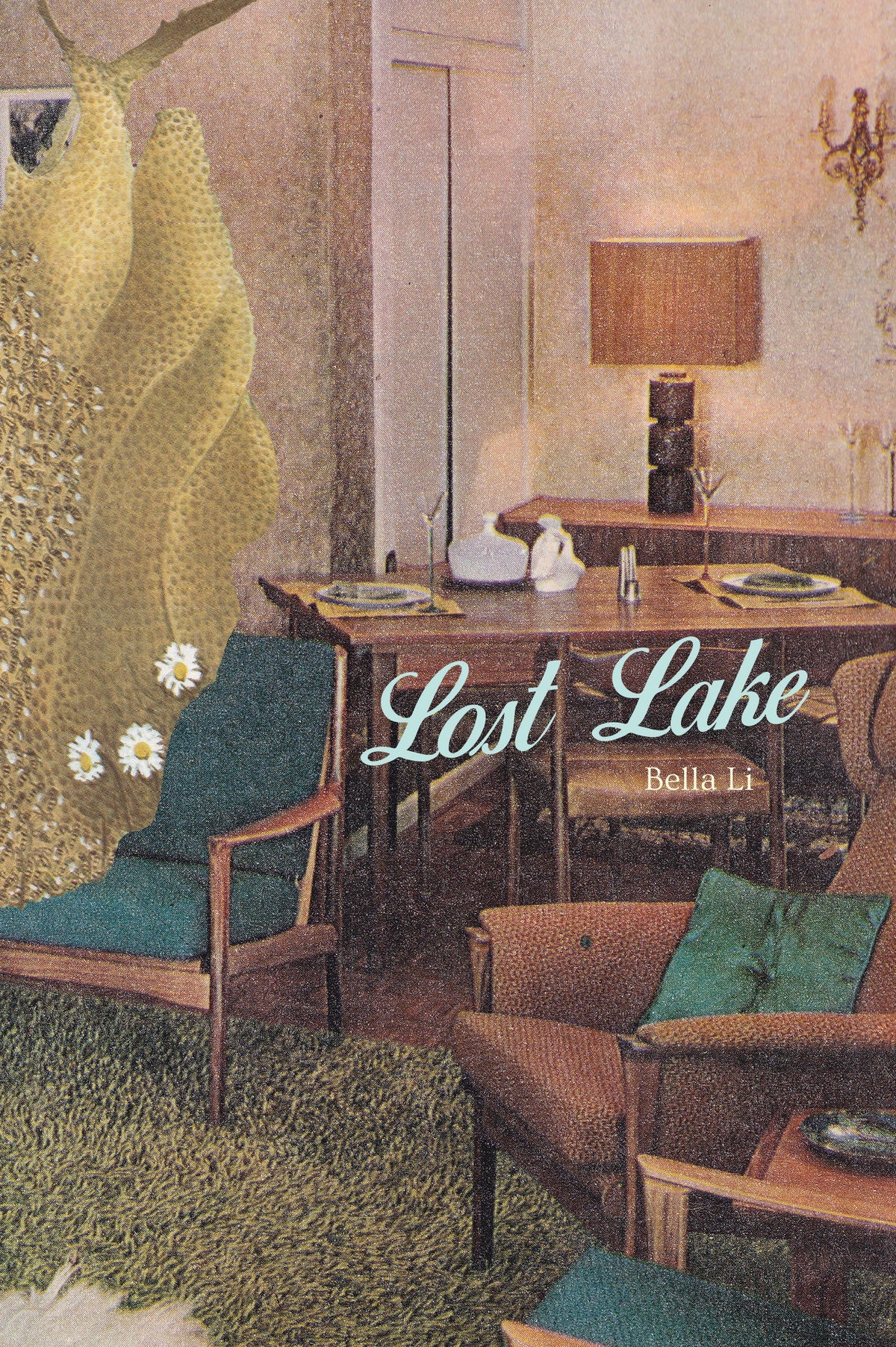

In the first sequence, absence or — the Witch —, which instructs us that “the absence of the Witch … does not Invalidate the spell,” archival domestic scenes are rendered strange by intrusions. They include eggs, honeycomb, diagram of the bees’ honey dance that takes the place of the faces of a sitting couple. The collage playfully suggests analogues between our concepts and theirs; what is a dance but communication? How does a bee know the world — and how do we? What might a bee describe as witchcraft?

Collage is a way of seeing several things at once, but imperfectly, because one image might cover another. Deciphering them is a stratigraphic skill. The second sequence, CIRCLES (A Parable), suggests this layering not just in its geological focus but in the relationship between word and image. Li notices resonances between elements of vastly different material: fountains of lava and falls of water. Layers of images and words produce unconformities or faults, where the continuity that connects time and geology have been eroded. So countries on opposite sides of the world are brought next to each other (“that’s what love was like — that old seaside holiday in England. All over Mexico”) and deep time sits alongside the present (in London “the river was there. Black shapes crouched between the trees”).

If some of the words feel familiar — I felt I knew lines in the last sequence, The Star Diaries, from Blade Runner 2049, The Road, perhaps The Parable Of The Sower — it’s probably because they are. In notes Li lists texts from which phrases are sourced, like sediment eroded from mountains to be deposited in new arrangements downstream. This sequence charts a series of post-apocalyptic journeys, cobbled from existing ones, to suggest their essence. “I remember him standing there in the shadows of the firelit room, barefoot,” Li writes, but it is not a comforting scene. There is radiation; the “quiet zero weather” is menacing. Later we visit a submerged city, “drifting over former libraries and museums, all sunk beneath the jelly-green water” while there are “silt tides accumulating in dense banks beyond the concrete reef”. Li’s voyager wrestles with hope and despair in this world, “upon this desolate rock, I abandoned myself to fate” but then “I began to think of how to make the best of what remained”. Images move from a ruined black-and-white forest into a construction like a habitat, where finally colour reappears.

“In the sky above no common satellite. No lode and no grace,” Li writes in this sequence, “Under the alien moon he stood, alone in the most beautiful place”. These are words that evoke the awe and terror when faced with the essence of the universe. Li finds this sublime throughout Lost Lake. In the eerie title sequence, photos document a body of water. There are splashes of ill-looking yellow, the water is silty, there are slumps of gravelly debris. Are we looking at some kind of disaster, perhaps natural, perhaps not? In DEFINITION OF THE FRONTIERS, the poet seems to draw from foundational memories, an impression reinforced by the images of amusement parks, which also suggest the spaceships that will later take our voyager to space. GRAND CENTRAL feels like it charts a whole industrial century, images of train stations collaged with anatomical drawings, vessels like beams and beams like vessels, tissues and materials. In one, a parent and child holding hands beside a train are just visible; there’s a diagram of the anatomy of a hand. Later the words take us to 1940, “the beginning of it all or the end. I see the precise geometry of his hand. The one held under the trees, after the bus.”

In an untitled sequence, Li draws from the archives of artist Joseph Cornell, in whose tradition of assembling Li is working in. In it, Li writes of a house where “nothing belongs”, “from which you could see the river”:

I want to describe its geometry: an enormous hall.

Each bedroom full of unknown people and strange birds.

It has been raining without end — water covers the earth, lightning and thunder.

The telephones don’t work.

Li explores these interiors further in Confessions, in which she wanders “the vast courts of memory, the caverns of the mind.” Confessing that “in my father’s house was a strange unhappiness … the soul of a man riveted upon sorrows,” she discovers the occult powers of books and their “corporeal fantasies”. Images layer snakes with fantastical architectural designs for a mausoleum for Newton. Like Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights, Lost Lake is an account of journeys, whether into the body and mind or into time and space, all intimate and vast, terrifying and wondrous.

Gay rating: not gay.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 Comment