Fittingly for a story that has the idea of “Australia” in its scope, this ambitious novel starts with an inferno. Five men in costume, “drunk on cider and violence”, start a week-long blaze in the fictional town of Bodkins Point that consumes the home of former Olympian archer Joy. It also kills her granddaughter Hannah. As the grief-stricken and long-suffering Joy (“fuckwits had plagued her her whole life”) collects herself and prepares for vengeance, the town prepares for its annual Agincourt, a “muddle of Shakespeare, Robin Hood, King Arthur and footy teams” (you could add: Lord Of The Rings, Game Of Thrones, and a dash of Kath And Kim). It’s a bloodthirsty ritual dating back to the town’s foundation that is an unholy combination of royal show and medieval reenactment. The townsfolk don helms, armour and real weapons, becoming their own Ned Kellys, heroes in a myth their own making.

The week-long festival was the brainchild of the settler Captain Bodkin, who planted the town’s first apple orchards and founded its cider dynasty. Subsequent descendants (“kings”) oversaw the event with varying levels of commitment to the rule of law and human rights. The townsfolk play their roles; Joy’s dad Conway (“an absent father who unfortunately hung around annoying you all day”) was the notorious Bugger Bandit, stealing from attendees and demanding their money or their life. Agincourt was where Joy was discovered as a child prodigy archer, a talent Conway exploited.

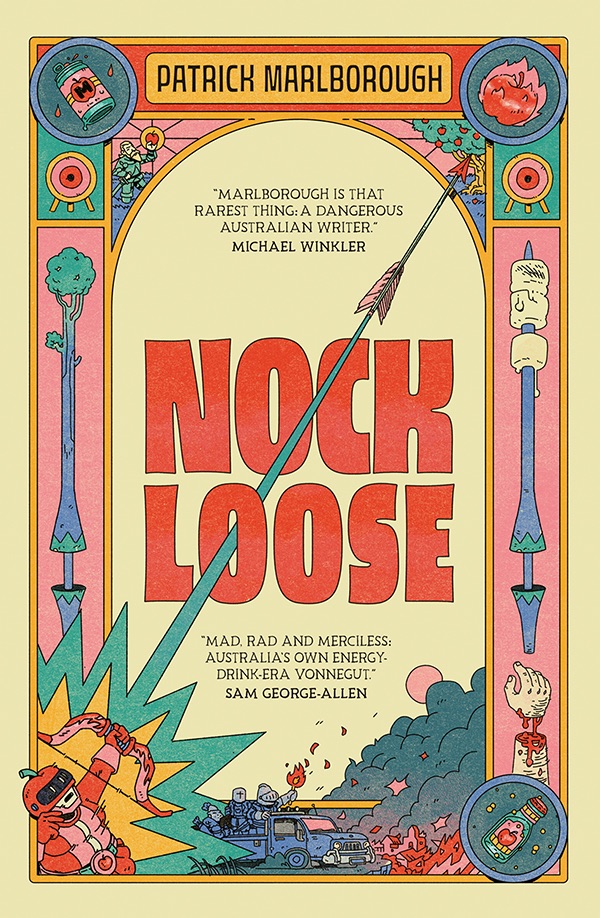

Like the myths and meanings (to misquote Geetanjali Shree, once you have an apple and an arrow, a story can write itself), the characters and plots proliferate: industrial disputes, bikie gangs, succession feuds, corporate takeovers, blood debts, poetry with hidden meanings, with a detour via the Japanese manga series Sukeban Yumi in which Joy played stunt-double for the series’ villain. A family new to Bodkins Point threatens to upset the status quo with talks of a mass grave of Noongar people. Many events circle the notorious Summer of Ash in 1969. There’s so much going on, at such density and speed —like Joy’s archery technique, “you just nock loose, nock loose, nock loose” — that it threatens to overwhelm like a barrage of arrows.

Marlborough hits the mark with their observations of the pride and larrikinism of the Aussie town, often in the details. Bodkins Point is a place where the inevitable lolly store is called Kountry Kandy Klassiks, and where the organising committee adopts the name BodCoin for its new cryptocurrency (replacing Tinnies; literally bottle caps) because “BodBucks is just silly”. When Marlborough unleashes the chaos of Agincourt, Nock Loose sings with absurdity and wit:

the crowd heaved with the music, rolling up and over itself like a sheepdog humping the wheel of a tractor being driven by the world’s drunkest farmer.

Like all good clowns, Marlborough is serious about silliness and silly about seriousness. Agincourt is like a grand final or the Melbourne Cup, a cathartic ejaculation of energy and emotion. But the celebration of larrikinism ignores the fact that the misbehaviour continues quietly all the rest of the time, in the violently banal structures of the colony. Marlborough demonstrates the continuity: this apple is rotten to the core. At Agincourt, no-one is really acting; the folk of Bodkins Point, Marlborough writes, are “obsessive role-players”. Aren’t we all in this fiction of a nation.

Gay rating: 4/5 for numerous queer characters and relationships (no furries).

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.