“One day”, Debra Dank writes in the introduction to Ankami, “I received a bundle of much wished for information from the National Archives”. That information confirmed in a handwritten note from a despicable man something Dank had long felt: four of her father’s siblings had been stolen from the station where they were born in what is now the Northern Territory. That note is the beginning and the end of the archive’s information on her aunts and/or uncles, so far at least. But is not the beginning nor the end of the loss that echoes through these pages.

Dank recounted some of her father’s story, and the abuse of his mother at the hands of the station owners, in her first book, We Come With This Place, an often joyful account of family and cultural continuity in the face of violence. While still lit with Dank’s loving memories, Ankami is like a shadow, an exploration of the unbearable. By the 1930s Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory were under the absolute control of the Chief Protector, and the territory was being used as a training ground for assimilation. Children of Aboriginal and white descent were removed from their families to be trained for cheap labour. This was just one part of a wholesale effort to destroy Aboriginal people and culture that also included certificates of exemption offered to some Aboriginal families who promised to give up culture in return for limited benefits. As Dank writes of her father and grandmother:

Those who stole our place utilised my family’s attachment to home to secure a largely unpaid — but not, it continues to be claimed, enslaved — workforce. This was the practice across too many places in Australia. This is not such ancient history, but it raises too many hard, pointed edges and so the conversations don’t happen, because the words that should be used, such as slavery, poison, violence, rations and massacres, are too big for modern-day sensibilities and fragilities.

Ankami is a work of truth-telling, vital in what it testifies about our history but also where we are now, when Aboriginal children are still being removed from their families at horrifying and increasingly disproportionate rates (in Western Australia, Aboriginal children make up nearly 60 per cent of all children in out-of-home-care, up from 35 per cent two decades earlier). Dank describes this inability to acknowledge truth as a double standard. How can Australians be “such decent world citizens,” she wonders, when they are also “directing me to move on, to forget and get over it.”

Epistemic violence is a wonky term from the realm of academia, but here you might actually feel it, the war waged not only against people and Country but knowledge and knowing. In this Dank builds on the archival work of other First Nations writers, such as poet Elfie Shiosaki. Despite the joy Dank discovers in written texts as a child, she also describes writing as “little black marks with their scratching lines and screaming curves … I hate them for their power and for their apathy about the outcome of their screaming. She describe how the “telling gaze” of white Australia:

often sees from elevated, distant places, not from within. It casts its own shadow over the story it tells itself and so feeds itself with truth-claiming falsehoods and ghosts. And in the shadow, the first peoples learn their new names and being — noble savages, Aboriginal and more — to become like faceless crowds. Rich and long-enduring lives are boiled down until their bones are exposed to become vacant symbols, with the fire of culture smothered under blankets of occupation, simplification, and even protection acts.

Her family’s movements were described as “nomadic”, part of the great lie of terra nullius:

that false naming in the new language split the world in two — settled and wild, civilised and primitive — but that split is not real. It is a shadow cast by colonisation. We were never lost in this land. We were and remain at its heart.

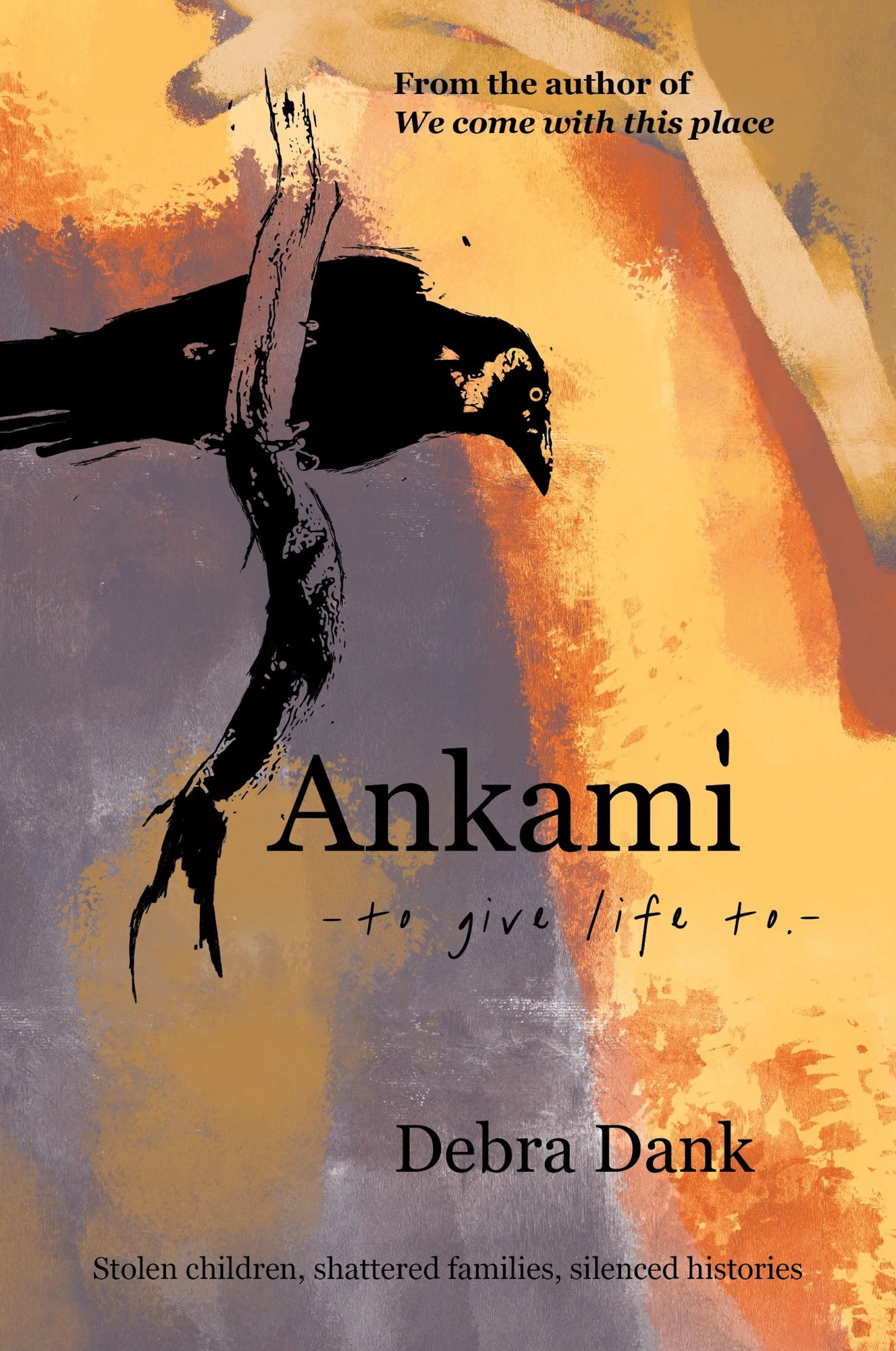

Elsewhere Dank distinguishes between information, which “can be Googled or read in books that have been written by others”, and culture, which is “absorbed”. Dank evokes her encounter with the archive — its silences and its violence — viscerally. But what is the colonial archive in the face of cultural knowledge? “You don’t just hear a story,” Dank writes, “You inherit it”. Ankami, subtitled “to give life to”, Dank wonders at the “What might have been, what could have been?” and “What should have been” of the lives of her stolen relatives, an aching process of anger and grief. She writes of ways of knowing Country that do not belong to us white Australians, that may rightly remain inaccessible to us, yet are surely something we must strive to listen to with the humility and respect that Dank asks.

Discover more from The Library Is Open

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 Comment