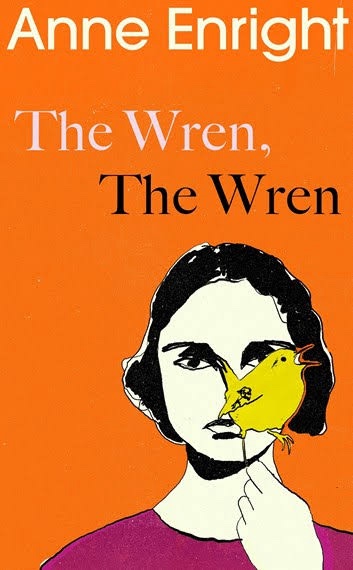

There are “great variations in way our inner lives play themselves out in our heads,” narrator Nell notes at the beginning of this novel. Empathy, “the solution (it is! It is!) to pretty much everything”; “it’s just like melting,” she says with the irony and knowing-ness that much-lauded empathy is often brought to the defence of fiction but is perhaps exaggerated. In The Wren, The Wren, Irish novelist Anne Enright explores the limits and possibilities of slipping into another person’s shoes.

Broadly the novel follows Nell, a 20-something “content creator” in Dublin, as she recounts falling in love with Felim, a hot country lad she encounters browsing magazines in a newsagent and decides he “looked real”. Red flags abound, but the sex, or at least the pillow talk afterwards, is intriguing enough to keep Nell coming back for more. Felim makes Connell from Normal People look like a manic-pixie-dream-rugby-boy (all young Irish romances are now inevitably post-Rooney), although they share a certain wistful yearning. Enright takes a pin to that fantasy. Felim, despite or perhaps because he doesn’t have a lot to offer, quickly becomes controlling and abusive, leaving Nell confused, numb and hurt.

Here the novel shifts to the perspective of Carmen, Nell’s mother (one of those mother-daughter relationships where the daughter calls her mother by her first name), recalling the day her father Phil, a minor Dublin poet, walked out on the family. Phil’s poems intersperse the chapters. They are seemingly innocuous, Romantic things, many of them translations of old Gaelic poetry, full of nature and fairy things and birds, including the wren of the title, “she was mine”, which appears to be a dedication to his daughter. The novel has already put you on high alert against such nonsense, and it becomes an excoriating portrayal of the generational wounds men do to women.

Enright explores that theme with ruthless clarity and brutal humour over the course of The Wren, The Wren. Imagining the inner lives of men, Nell notes blackly that they’re thinking of football when they’re not thinking about where to put the bodies of their murdered girlfriends, and “somewhere under the football … the bang of a blue sky on some far planet (he is a boy, remember)”. She adores her grandfather without initially understanding the legacy he has left for her mother and perhaps for herself. Not that Nell and Carmel lack agency. Nell at least initially feels Felim is a choice to be treated badly. “I want something more incidental, unperformed. I want worse,” she says. Carmel spends most of her life going to great effort in the attempt to avoid the control of men. But it’s hardly a level playing field is it, and Enright’s sting in the tail is to explore how men get away with it and how the limits of our ability to imagine the inner lives of others might prevent attempts at resistance. Through the novel’s free-wheeling structure Enright exposes these generational patterns.

Enright’s immaculate writing switches between faux poetry and Zoomer angst with the spryness of one of the numerous birds that flit through the novel, symbol of bounds and boundlessness. It is wonderfully alive, airy prose, by turns conjuring the wonder of Helen MacDonald (there’s more than a little of MacDonald’s way with nature in Enright’s descriptions of the environment), by others the nihilistic absurdity of the internet’s weirdest corners.

Gay rating: 2/5 for some queer characters.