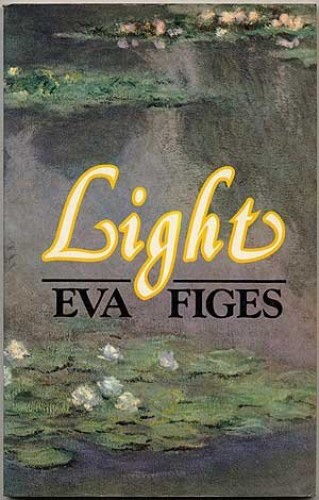

A lots of us have found our worlds smaller due to the pandemic. One thing this shrinking world has made me do is pay attention to things closer at hand. I watch the comings and goings of insects on our balcony, the different birds showing up in the local parks, the creeper making its way slowly up the lattice. We’ve noticed how the light strikes the walls in different seasons and different times of day. Light, feminist and author Eva Figes’ exquisite short novel published in 1983, is similarly about seeing things more intimately.

Light takes place over a single day at Claude Monet’s home in Giverny. The artist rises early in the dark, making his way down to the river to paint the blue light of dawn. His family and servants stir around him, the maids in the kitchen, the gardeners who assist him. It’s a day in the life, so nothing much happens, except everything. Alice, Monet’s second wife, is still wearing black for her daughter Suzanne. Visiting her grave in the village cemetery at dawn, she finds that “this was her home, and … the effort of pretending otherwise was becoming too much”. Suzanne’s children, little Lily and Jimmy, stave off boredom playing the in garden. Germaine, Alice’s youngest, dreams of betrothal to Pierre. “Fat, solid, dependable Marthe, who would vanish into thin air if nobody needed minding, or nursing,” wonders if she will ever have a role beyond glorified servant. The writer Octave Mirbeau visits for lunch. Although unspecified, the year must be 1900 or 1901, a year after Suzanne’s death, giving the novel a turn-of-the-century atmosphere.

Light is simply what Monet’s version of Impressionism looks like in literary form. It is about light and time, the two subjects of the Parisian movement the emerged in the late 1850s with artists such as Renoir, Degas, Manet, Morisot and Pissarro. Impressionism, at its heart, was about capturing a moment in time, and was associated with methods like painting outdoors and subjects like street scenes and everyday people. These ideas are ubiquitous now, but were revolutionary at the time. Of all the painters, Monet had perhaps the most feeling for light itself, which culminated in his immense waterlily panoramas. “I have you,” Figes’s fictional Monet thinks, “all of you trapped, earth, water and sky”. It is equally hard to separate his garden from his painting; it was in effect an extension of his paintbrush.

Each time I encounter Monet’s paintings, most recently at the National Gallery of Victoria’s excellent Impressionists from the Boston Museum exhibition, I try and fail to capture their effect. They vibrate, they shimmer, they are what light itself looks like. Figes’s novel gave me the same feelings. It is easy to understate the achievement, because it is so effortless. Light and shadow play incessantly across the pages. Figes treats them as separate physical phenomena, material things that alter what they touch, not one the product of the other. The only other book I’ve read that even attempts something similar is Maaza Mengiste’s The Shadow King, which does a similar thing with 1930s war photography.

What can writing bring to something that the paintings do so well themselves? Something that Monet’s paintings can never do, give us context and other perspectives. Each of the characters have their own quiet moments of revelation; each of them notice different things about the light. While Monet hunts the bright instant, Alice is confined to the eternal shadows, and the other characters are arranged between these two poles as if on a spectrum. While Monet’s paintings can only suggest the gendered world they were created in, Figes shows the female labour that allowed him to do his work. Monet is a distant husband and father, and something of a tyrant, his children and servants tiptoeing around his needs. Change, social and technological, is afoot. Monet is contemplating both an automobile and a telephone, two recent inventions that Mirbeau poignantly suggests will render war redundant. “How can they make us go to war against a man when we have toured his country in our automobiles, and he ours?” he pontificates, “How can you kill a man when you can speak to him on the telephone?” In such moments Figes captures the hope and naiveté of every time.

The writing is mostly descriptive, and as exquisite as you could hope for with such subject matter. Here’s Monet and Mirbeau walking through a meadow in the late afternoon:

A cloud shadow moving over the grass turned it suddenly amethyst, the light of buttercups went out like candles as the shadow of amethyst moved across them, poppy heads died as slow-glowing embers, the grass had become a shuddering slipstream of cool blues and greys, clover-coloured, deep and mobile as the river beyod.

Because it is so short, each word is freighted with meaning. As Monet sees the light catch on the shrubbery as he “touched a petal on the burning bush and thought of the extraordinary theory of atoms”, evoking the Bible and physics in the same moment. A single, easy-to-miss instance of present tense likewise effectively demonstrates what the Impressionists sought.

Light is a book for a certain mood. Like walking around a garden, it cannot be rushed, even though it is small. It requires a stillness of mind, even as it leads you to that stillness. While reading, I began to see things in a different way, noticing the light and shadows in my apartment, how they were different intensity and colour, how they moved. It may not be for everyone, but I found it a lovely, meditative reading experience that, while it lasted, allowed me escape and transport, those simplest and easiest to underestimate pleasures of reading.

Gay rating: not gay.

2 Comments